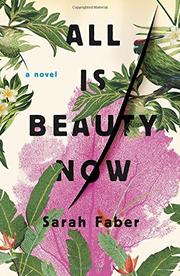

All Is Beauty Now Sarah Faber (2017)

Historical facts that I learned from this novel: After the American Civil War, somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 Southerners fled to Brazil, where slavery was still legal and where the Brazilian government offered them incentives to settle. These immigrants, called the Confederados, and their descendants lived in enclaves, mostly near Rio de Janeiro and Sấo Paulo. Although there was considerable intermarriage with Brazilians over the decades, Confederados were an identifiable ethnic group in Brazil as late as the 1960s and 1970s.

Dora, a descendant of Confederados, is married to Hugo, a handsome Canadian engineer. They live outside Rio and have three daughters. In the opening pages of All Is Beauty Now, the eldest daughter, Luiza, disappears while swimming in the South Atlantic in March 1962. Canadian novelist Susan Faber slowly unfolds the back story to this disappearance, probing deeply into the psyches of each of the five members of the family. The chapters move forward and backward in time and switch off among characters. It soon becomes apparent that Hugo’s mental illness is a catalyst for many other actions in the plot. Hugo would likely be diagnosed today as having bipolar disorder, but in the early 1960s the term did not exist, nor did effective treatments.

I dipped into All Is Beauty Now over a period of several weeks, soaking up descriptions of the white-sand beaches and lush gardens, the wild riotousness of Carnival, the extravagance of the nightclubs in Rio. Hugo finds that, compared with Canada, “Rio was a demented Eden, crackling with newness and feeling . . . Here, below the equator, as the Brazilians say, there is no sin.” (37)

Beneath the surface issue of Luiza’s presumed drowning, Faber analyzes, perhaps in too much detail, the effect of Hugo’s mental state on his family and on others around him. The question of drug treatment for Hugo is fraught. For example, in a flashback, Luiza asks herself, “What if the doctors stripped away his moods, then found there was nothing left?” (55) As the family prepares to move to Hugo’s native Canada to seek better care for him, Dora muses on the luxury of having servants in Brazil: “When the Confederados arrived in Brazil, her father told her, they found cockroaches the size of a fist, and mosquitoes carrying dengue, malaria, encephalitis. A third of her ancestors died; a third went home, and accepted Northern rule; a third stayed, thrashed and coaxed the landscape. And now she, their descendant, can do almost nothing for herself, by herself. Some part of her is grateful that Canada will be hard. Perhaps all that labour will wash away the slick sheen of her advantages.” (260)

Faber’s prose ranges from languid to exotic in this melancholic novel. The pacing of this novel is very slow, totally unhurried, like a drowsy day on a magnificent beach. But the ocean can sweep anyone away with cruel rapidity.