In this second installment about books from the New York Times list of the best books published since the year 2000, I offer condensed versions of reviews that I’ve posted on this blog over the past seven years. These titles have won numerous national and international literary prizes.

The Goldfinch Donna Tartt (2013) A young man named Theodore Decker loses his mother in a terrible explosion. What follows is at once a bildungsroman, a mystery, a thriller, and a wild drug-fueled ride through a speculative alternate history of New York City. But you can read its nearly 800 pages solely for Tartt’s extraordinarily lush vocabulary and sympathetically drawn characters.

Pachinko Min Jin Lee (2017) In this novel about Korean immigrant families in Japan during the twentieth century, Lee lays out the Japanese discrimination against Koreans clearly. But she also includes both Koreans and Japanese who are deceitful and honest, talented and mediocre, wise and foolish, lazy and hardworking, compassionate and heartless, selfish and generous, prejudiced and open-minded. Subplots touch on issues such as the status of minority Christians and the evolving attitude toward the place of women in Japan. Above all, though, this is a universal story about the immigrant experience. Immigrants enter a game of chance, stacked against them, much like people who play pachinko, the popular Japanese slot-machine game.

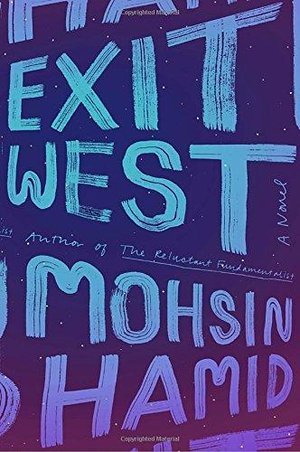

Exit West Mohsin Hamid (2017) Hamid is known for his experimental prose, but Exit West can appear to be a more conventional novel—that is, until you hit the magical doors. These doors whisk Hamid’s characters to another country, with some similarities to the door through which CS Lewis takes his characters to Narnia. But Hamid’s characters definitely do not end up in Narnia. They’re refugees, fleeing their unnamed native land, where “militants” cause increasing upheaval and danger. This prescient novel personalizes the plight of refugees—ordinary people who through no fault of their own are caught up in war and terrorism, who flee with great reluctance, leaving behind virtually all their possessions, clinging to the few family members who have not perished.

The Overstory Richard Powers (2018) The Overstory is massive in scope, sophisticated in descriptive power, and disturbing in message. Instead of framing his book as a nonfiction exposé of the sins of the logging industry, Powers has chosen to show the diverse motivations of fictional “tree huggers” from all walks of life. This approach is much more effective in getting across his message that the human destruction of forests will eventually, and pretty soon, make our planet unlivable.

Small Things Like These Claire Keegan (2021) With haunting prose that’s reminiscent of the early work of James Joyce, this novella fictionalizes a piece of the well-documented history of the Irish “laundries,” where unwed pregnant women were basically imprisoned by the Catholic Church until as recently as 1996. Author Keegan takes us to rural Ireland at Christmastime in 1985, when a middle-aged family man stumbles upon evidence of such human rights abuses at a local convent. I read everything that Claire Keegan publishes, and I’ve never been disappointed.

Trust Hernan Diaz (2022) Diaz explores the trustworthiness of narrative through four different takes on the same story, about a fictional early-twentieth-century Wall Street financier. First, a novella captures the style of Edith Wharton, and next, an unfinished autobiography reveals its author’s vanity and arrogance. A memoir by the autobiography’s ghost writer gives another perspective, and finally the diary of the financier’s wife provides a new twist to the tale. Diaz navigates these disparate genres with stylistic ease, as he asks, Whom do you trust to tell you the truth?