The Dutch House Ann Patchett (2019)

The Dutch house of the title is a mansion in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Cyril Conroy bought it for his wife, Elna, in the 1940s, when he amassed a large sum in real estate. He never asked her if she wanted it before the purchase. (Guys did that back then. Some still do, I guess.) The place was previously owned by a Dutch family, the VanHoebeeks, and their portraits and furniture still adorn it.

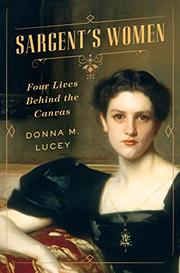

Elna hates the opulent life that her husband’s financial success has brought to the family, and she especially hates the Dutch house. She decamps, leaving Cyril with their three-year-old son, Danny, and their ten-year-old daughter, Maeve. (That’s supposed to be Maeve’s portrait on the book cover.) The children are taken good care of by a faithful cook and housekeeper until the wicked stepmother, who covets the Dutch house, and her two daughters enter the picture. Then all hell breaks loose.

Narrated in first person by Danny, The Dutch House skips back and forth in time over a period of half a century, as Maeve and Danny cling to each other and try to come out from under the power of that huge, overly ornate structure. The reader can’t help but have sympathy for two people who struggle with the fact that their mother deserted them basically because she couldn’t stand to live in the Dutch house, which their father wouldn’t give up. Or was that really the reason?

Small recurring themes, such as the repeated attempts of Maeve and Danny to quit smoking, enliven the story. “Maeve always said I smoked every cigarette like I was on my way to my execution, and I was thinking this really should be my last one. I knew better, even though those were still the days when doctors kept a pack of Marlboros in the pocket of their lab coats.” (277)

Ann Patchett delivers her usual assured narrative line as her highly believable characters ponder issues of forgiveness, revenge, and the bonds of family. Maeve and Danny are remarkably self-aware, despite their many questionable life decisions. Here’s Danny again: “There are a few times in life when you leap up and the past that you’d been standing on falls away behind you, and the future you mean to land on is not yet in place, and for a moment you’re suspended, knowing nothing and no one, not even yourself.” (121)

I’ve reviewed a previous Ann Patchett novel, Commonwealth, here. Patchett has legions of diehard fans, and The Dutch House will certainly be on their request lists. It’s also a very good choice for those unfamiliar with Patchett’s novels.